Strength Training Part 1: Introduction

Strength Training Part 1: Introduction

Strength Training Part 2: Hamstrings

Today's post is about hips & glutes. It's a long post, but frankly, in terms of bang for your buck when it comes to injury prevention, this is probably the most useful & important of this entire series. If you're only going to read all the way through one of them, I'd probably go with this one. As I learned from my PTs, it's the exceptionally rare running pain that can't ultimately be traced back to either foot strike or hip strength (excluding sudden injuries like twisting an ankle, of course).

My original plan was to do what I did for hamstrings -- start off talking about how everything works & where the injuries come from, then show some exercises. Hips & glutes are complicated, though, and by the time I finished all the "how stuff works," this post was already fairly longish. So I'm just going to post that stuff first, and then show the exercises in a different post. I am utterly fascinated by muscles & body movement & how everything works together (or doesn't), but if you're more the "just fix me" type, I won't be TOO offended if you just check out the exercises when I get them posted. ;)

(Quick Reminders:

- I am not a doctor/PT/trainer/etc.

- The info I have to share with you by & large comes from sports medicine doctors/PTs/trainers/etc. but has mostly come to me in the context of dealing with my own injuries.

- If you try anything and it hurts, stop & check in with a pro

- If you ARE a doctor/PT/exercise professional and anything here sounds sketchy or like I've misunderstood it, let me know so I can fix it!)

The Nuts & Bolts

One of the things I spent a lot of time working on when I was in physical therapy was what they call pelvic (or core) stability. Pelvic stability, as you might guess, refers to how much your pelvis wobbles around when you run.

The red dude has poor pelvic stability. When his left leg pushes off and leaves the ground, his left hip drops, causing his pelvis to tilt horizontally. When his right leg leaves the ground, his right hip will drop. You can see how this will cause a horizontal see-saw motion in his hips while he runs.

The blue dude has good pelvic stability. When his left leg pushes off and leaves the ground, his hips stay even. This means that his hips will stay level and even as he runs rather than see-sawing.

So why should you care about how stable your pelvis is when you run? Well, according to the physical therapists I worked with, poor pelvis stability accounts for a huge number of the running-induced overuse injuries they see. In my case it was hip pain right beneath the iliac crest, but apparently this is the kind of thing that can manifest in all kinds of exciting ways.

|

| What an unstable core/pelvis looks like in a real runner.

|

Me: "Ah, interesting. I'd been kind of wondering whether it was some kind of IT band syndrome thing or something."

PT, with a shrug: "Eh, it wouldn't have changed much. IT band syndrome is often pelvic instability too."

A few sessions later:

Me: "(Blah blah blah), a few years ago when I was having all this knee pain...(blah blah blah)."

PT: "Yeah, that was probably the same thing. Pelvic instability is a pretty common cause of knee pain."

A few sessions after that:

Me: "(Blah blah blah), medial tibial shin splints on & off...(blah blah blah)."

PT: "The overpronation & hypermobility is probably causing some of that, but a lot of times MTSS is just another symptom of pelvic instability."

A few sessions after that:

Me: "Hey, at least it's not piriformis syndrome!"

PT: "Yeah, guess what I'm going to tell you about that."

Me: "So what you're saying is that pelvic instability is basically what keeps you in business around here."

PT: "Job security, man."

As one of them explained it, all these diagnoses and syndromes that are out there -- ITB syndrome, piriformis syndrome, patellafemoral syndrome, etc. -- are all just extreme manifestations of the same underlying problem, and most patients fall somewhere along a multi-dimensional spectrum in terms of their particular symptoms. A runner with persistent hip/upper leg pain obsessing over "What do I have?" is asking the wrong question. The label you attach to it, he told me, is irrelevant, because most of those things have the same root causes. They could have written "Mild ITBS" or "Mild piriformis syndrome" or "Mild TFL syndrome" on my chart for all the good it would've done, but the treatment would've been the same. (Instead they went with "general hip dysfunction / not otherwise specified.") The important question is, "What is the underlying cause?"

Of course I'm not saying that every running pain you've ever felt in your life was a result of weak pelvic stabilizers. But I am saying that it's a problem that manifests in many different ways, and if you have a thing that's gone on a long time & you haven't had the whole pelvic stability thing checked out, it's maybe worth looking into.

Of course I'm not saying that every running pain you've ever felt in your life was a result of weak pelvic stabilizers. But I am saying that it's a problem that manifests in many different ways, and if you have a thing that's gone on a long time & you haven't had the whole pelvic stability thing checked out, it's maybe worth looking into.

So let's talk about your pelvic stability muscles. Today's cast of characters:

Hip flexors. These are the muscles that let you bend your leg or torso forward at the hip. The most important hip flexors are the psoas major & minor (fun fact: not everyone has a psoas minor, which I guess is why it's not in the picture), the iliacus, and the tensor fascia latae, or TFL.

Glutes. Your gluteal (butt) muscles let you move your leg backward at the hip. You can feel them working if you lay on your stomach and raise your leg backward up off the ground, keeping your knee straight. There are lots of gluteal muscles but the most relevant ones for us are the gluteus maximus ("glute max" for short) and the gluteus medius ("glute med," which you pronounce "glute mead").

Glutes. Your gluteal (butt) muscles let you move your leg backward at the hip. You can feel them working if you lay on your stomach and raise your leg backward up off the ground, keeping your knee straight. There are lots of gluteal muscles but the most relevant ones for us are the gluteus maximus ("glute max" for short) and the gluteus medius ("glute med," which you pronounce "glute mead").

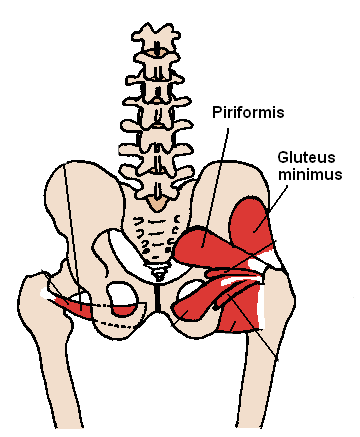

Piriformis. Trying to explain about the piriformis is kind of hard for someone like me who is not a pro at this. Wikipedia states, "The piriformis is a flat muscle, pyramidal in shape, lying almost parallel with the posterior margin of the gluteus medius. It is situated partly within the pelvis against its posterior wall, and partly at the back of the hip-joint." I'm going to tell you it's a little pear-shaped muscle deep in your butt muscles. If you stand up and raise one leg a little off the ground in front of you, keeping your knee straight, then try to rotate your whole leg out and backward at the hip, that's your piriformis working.

Piriformis. Trying to explain about the piriformis is kind of hard for someone like me who is not a pro at this. Wikipedia states, "The piriformis is a flat muscle, pyramidal in shape, lying almost parallel with the posterior margin of the gluteus medius. It is situated partly within the pelvis against its posterior wall, and partly at the back of the hip-joint." I'm going to tell you it's a little pear-shaped muscle deep in your butt muscles. If you stand up and raise one leg a little off the ground in front of you, keeping your knee straight, then try to rotate your whole leg out and backward at the hip, that's your piriformis working.

Iliotibial Band. I think a lot of people are under the impression that the IT band is a muscle. In fact, the IT band is a long, tough, fibrous piece of connective tissue that connects to the TFL and glutes at the iliac crest & to the muscles in the tibia at the other end. (Get it? Ilio-tibial?). The IT band is primarily made up of the same type of collagen fibers as your spinal discs, which which gives you an idea just how tough and strong it is. The main role of the IT band is to stabilize the lateral (side-to-side) motion of the upper leg/femur.

Iliotibial Band. I think a lot of people are under the impression that the IT band is a muscle. In fact, the IT band is a long, tough, fibrous piece of connective tissue that connects to the TFL and glutes at the iliac crest & to the muscles in the tibia at the other end. (Get it? Ilio-tibial?). The IT band is primarily made up of the same type of collagen fibers as your spinal discs, which which gives you an idea just how tough and strong it is. The main role of the IT band is to stabilize the lateral (side-to-side) motion of the upper leg/femur.

How Does A Wobbly Pelvis Cause Running Injuries?

On the left is an example of more or less what your lower body is doing during the support or stance phase if you have a stable pelvis (except that my left leg should really be pushing backward, like in the other picture...sorry). Notice that my hips are level and my right knee is pretty close to directly under my hip. (It is harder for women to align our hips & knees perfectly since we tend to have wider hips than men, but this is pretty decent.) On the right is a slightly exaggerated example of what it's doing if your pelvis is not so stable.

See how in the unstable version my right hip is popped out slightly to the side, my left hip is dropped, and my right knee is (kind of) collapsing inward as it bends? (I've spent so much time working on fixing this that it was really hard for me to do the collapsing knee intentionally, so this isn't the greatest picture for that.) These are the telltale signs of weak hip abductors, the muscles you use to lift your leg sideways away from your body (as opposed to the adductors, which you use to squeeze your thighs together). The prime mover (the muscle that does most of the work) is the glute med, & the synergist muscles (the ones that assist & help control the motion) include the psoas, piriformis, & TFL. These muscles control the IT band, which keeps your femur straight and your hip and knee in alignment.

Here's another picture that shows the collapsing knee idea a little better:

It's this lateral motion of the support (touching the ground) leg that causes so many problems in runners.

- IT Band. The IT band tries to stabilize all the wobbling & tilting of the femur, but it can only do so much. Overtaxing the IT band pulls it in a way it isn't really designed to go, causing the underside to rub against some of the knobby bony parts of the femur & resulting in irritation & damage (think of a rope fraying as it's pulled back & forth across a rock). Scar tissue forms where the damage happens, causing a) tightness (scar tissue is tougher & less flexible) & b) more pain (scar tissue is nerve ending-rich).

- Lateral Knee/Hip. A tight/overworked IT band can create pain & tenderness where it connects to the TFL and glutes (the problem I had) or where it connects to the tibial muscles on the outside of the knee (the more standard ITBS symptom).

- Patellafemoral. When the hip pops out and the knee collapses inward, a misalignment of the knee joint results. This makes it hard for the patella to slide smoothly over the patellar ligament that connects the quads to the lower leg. The ligament rubs against the underside of the knee cap, causing pain & swelling. (A lot of times this is referred to as 'runner's knee' or patellafemoral syndrome.) This is the problem I had several years ago.

- MTSS. This collapsing of the knee inward also creates what's known as induced pronation, and probably accounts for a lot of the orthotics & stability shoes out there. Knee collapses in -> lower leg follows knee -> ankle follows lower leg -> foot follows ankle & rolls inward. Excessive pronation is one of the most common causes of medial tibial shin splints. (I've dealt with this on & off for most of my running life.)

- Piriformis. If the glutes & hip muscles are too weak to control the lateral motion of the femur (resulting in all this hip dropping & knee collapsing), the piriformis will often try to compensate for it. Because it is a synergist muscle when it comes to hip abduction and not a prime mover, it isn't really strong enough to do this, and the result is same as with the IT band -- damage, scar tissue, tightness, and pain. We call this piriformis syndrome.

- TFL. On the anterior side, the same thing can happen to the TFL (also a synergist in hip abduction). It tries to compensate for the inability of the stabilizer muscles to do their jobs and ends up sore and tight (TFL syndrome).

So what causes all this lateral motion in the upper leg?

It's the job of the IT band to stabilize the femur & keep it moving in a fairly vertical plane between the hip and knee. But remember, the IT band itself is not a muscle -- it's connected to the TFL and glute med. So really, it's the job of the glute med (and its synergist muscles) to stablize the femur via the IT band.

When the glute med, et al. is strong, it's able to use the IT band to keep the femur square and prevent the support knee from collapsing inward. When it's not strong, it can't do this (or can only do it for a little while). It's just the physics of the motion that cause the leg to want to roll in in this way, but when the glute meds & synergist hip abductors aren't strong enough to limit that motion, you get the problems above.

The upshot: If you're going to do any amount of serious mileage, your glutes and hip muscles have to be strong.

Why are weak hip abductors/glutes so common in runners?

Running is primarily a front-to-back motion. Our legs get a lot of work in that direction but almost no work in the rotational / side-to-side direction. Yes, our hip abductors will still work to try to stabilize the lateral motion of your legs through that front-to-back motion, and if you don't run all that much, they might be able to handle it. But the more running you do, the sooner those hip abductors are going to get worn out and overused. This is why paying special attention to strengthening your hips and glutes goes hand-in-hand with building mileage.

Secondly, weak hip abductors/glutes are common in runners because they are common in first-world people in general. It's just a fact that most humans, even those of us who are active a lot, spend a lot of time sitting. I mean, think about a recreational athlete with a typical commuter/office job. Half an hour sitting in the car/bus/train/etc. on the way to work; let's be generous and supposed she manages to spend a grand total of two of the nine hours she spends at work standing or walking & spends the other seven sitting in front of her computer or in meetings; half an hour sitting on the ride home. Again let's be generous and suppose she finds two hours on average in her evening to exercise and be active and do things like make dinner that involve standing and walking. Then maybe she spends three more sitting at the table for dinner, relaxing on the couch, helping kids with homework, sitting at her computer checking email/paying bills/etc., or sitting up in bed reading before she goes to sleep. That's 8 hours sleeping, 4 hours standing/walking/exercising, and 11 hours sitting. (Divide up the remaining hour however you want.) And that's an ACTIVE person who prioritizes exercise.

So what's the problem with sitting? Remember how we talked in the hamstrings post about how complementary muscle groups (muscles that move the same joint in opposite directions, like the biceps & triceps for your elbow) should ideally stay equally strong & flexible, and how imbalances in complementary groups can cause overuse injuries?

When we sit, our hip flexors are shortened and our glutes are lengthened. When we stand, it's the opposite. Our ancestors living on the African savanna three million years ago had a much better balance between the two, resulting in (surprise!) fairly balanced hip flexors & glutes in terms of both strength and tightness. These days, though, even for active folks, tight hip flexors and weak glutes are the norm. (BTW, lower back pressure/pain? Probably the same cause.)

Do your hips/glutes need work?

The simplest DIY way to test your hip/glute strength is with the single-leg quarter squats that I used above to demonstrate a stable pelvis vs an unstable one. First, make sure you're wearing something where you can clearly see what your knee and pelvis are doing (probably not pants, and a top that leaves at least the waistband area of your shorts visible). Stand in front of a mirror and lift one leg off the ground. Note the angle of your waistband -- at this point it should still be pretty much horizontal. Now slowly bend your support knee until you're about a quarter of the way to a full squat position.

The following are red flags that can indicate weak hip abductors:

- You can't do the squat at all (ie, you don't see how you can stand on one leg and bend your knee and still support your body weight). The first time I tried to do it, I was sure I had misunderstood the instructions because it seemed so completely impossible. Nope; I'd just lost a ton of muscle tone in my glute meds.

- Your knee doesn't stay in alignment with your hip and foot and instead moves inward. (Like I said above, women get a very little additional leeway here, but not much.)

- Your knee/leg trembles or wobbles as you move through the squat.

- The hip on your suspended leg drops instead of staying level with your support hip (sometimes it's easiest to see this by watching the waist band of your shorts -- if it tilts as you squat instead of staying parallel to the floor, the hip on your suspended leg is probably dropping)

- The hip on your support leg pops outward as you squat

Another thing they had me do a lot in PT is jump off of a small box and freeze as I landed. The box was not tall, maybe 18 inches or so, and my instructions were to bend my knees a little to absorb the force of the landing while keeping my back straight as much as possible (ie, not leaning over too much). To assess my hip abductor strength, they would look at what my knees did when I landed. If they stayed pretty much square over my feet as they bent, then my glute meds, et al. were strong enough to do their job & use the IT band to stabilize my femurs and knees. If they collapsed inward, that was an indicator that they still needed work.

Left: A strong, stable landing with knees more or less directly over feet.

Right: An unstable landing with knees collapsing inward.

Last but not least -- Eccentric Strength & Shock Absorption

Your muscles are capable of two types of contractions: concentric, where the muscle shortens (ie, bending your elbow to lift a weight toward your shoulder), and eccentric, where it lengths under a load (ie, gradually straightening your elbow to lower the weight in a smooth, controlled motion rather than just letting your arm fall). Eccentric and concentric are two different types of strength that don't always go hand in hand. You can have good concentric strength in a muscle but poor eccentric strength, or vice versa.

For runners, eccentric strength in the glutes & other hip abductors is essential for preventing injury. When you run, your foot (hopefully) lands directly beneath your hip in order to reduce braking forces and direct most of your energy horizontally and into forward motion rather than vertically down into the ground. Still, even the most beautiful foot strike the world has ever seen will generate some amount of downward force, which in turn generates upward force from the ground to the foot (Newton's 3rd). All that force has to go somewhere.

Concentric strength in your glute meds (as well as most of your other leg muscles) is important for running because that's what you use to push off the ground and propel your body forward. Eccentric strength, on the other hand, is what lets those same muscles lengthen in a smooth and controlled way when your foot hits the ground and your ankle, knee, and hip bend to safely absorb and distribute the upward forces from the ground. (When you do the slow, single-leg squats described above, you're using eccentric strength on the way down and concentric strength on the way up.) Having poor eccentric strength means that instead of gradually lengthening to absorb the force over more time, the muscles lengthens more suddenly, meaning they absorb less force. And the less force that gets absorbed by eccentric muscle contractions, the more ends up channeled into ankles, shins, knees, hips, spine, etc.

To get a better sense of this, think about what would happen if your biceps did not have the eccentric strength to slowly lower a barbell in a controlled way, and instead you could only drop your arm & straighten your elbow suddenly. Instead of the force slowly getting absorbed by your biceps over time, most of it is absorbed suddenly by your elbow joint & its various connective tissues. This is often the mechanism by which “too much / too fast / too soon” leads to strains, stress fractures, & other overuse injuries.

"Think of your muscles as cushions," one of my PTs told me. "The stronger they are, the more they will protect your bones, joints, and connective tissue."

Testing Your Eccentric Strength

Again, the single-leg quarter squats are great. If you're able to slowly lower your hips (keeping them square) a quarter of the way to a full squat without too much shaking or trembling, the eccentric strength in your glute meds is probably pretty good. If you can't do it, or can't go very far, or your knee & femur wobble as you do it, you could probably use some work in this area. (I was not discharged & cleared to train again until I could do 50 in a row on each side pain-free.)

A few other things they constantly looked at when I was in PT included:

- Vertical hip bounce while running. I would run on a treadmill while they videotaped from the side, and then we would watch to see how much difference there was between the highest point my hip reached in a stride and the lowest. A few inches was okay, but more than that meant that my entire pelvis was dropping as each foot hit the ground because I didn't have the eccentric strength in my glutes to control the downward force.

- Loud/quiet foot strikes. From my first weeks, they coached me to "run whisper-quiet." Barely audible foot strikes indicate that force is being absorbed & distributed efficiently & safely, while easily audible pounding/slapping indicates poor absorption due to poor eccentric hip/glute strength.

- Loud/quiet landings on the box jump. Remember how I mentioned they watched me jump off of a box a lot & watched to see what my knees did? They also listened to how loud my feet were when I landed, for the same reason as they did on the treadmill. A soft, quiet landing meant good absorption & eccentric strength, and a loud landing meant I still needed work.

Whew! If you made it all the way through that, then good on you. Hopefully you found at least some part of it informative and/or useful.

For all that I would have loved to avoid four months and many hundreds of dollars in physical therapy last year, I still feel very fortunate to have gotten a chance to learn so much about the details of how running works and how to continue doing it while taking care of my body. In the next post, I'll show the strength exercises I still do, even many months later, to keep my hips and glutes strong and pain-free.

This is my weekly training journal. Including it in the blog gives me a little extra accountability in the mileage department & helps me stick to my schedule. :)

This is my weekly training journal. Including it in the blog gives me a little extra accountability in the mileage department & helps me stick to my schedule. :)

1) I finished reading

1) I finished reading  2) I found out that I was being tested for 1st kyu on Feb. 6th. (Note: It's over and I passed! :) ) Kyu ranks are student ranks and go from 10th (white belt) to 1st (3rd degree brown belt). 1st kyu testing is kind of a big deal because it's the last one before black belt. #hardcorefighting

2) I found out that I was being tested for 1st kyu on Feb. 6th. (Note: It's over and I passed! :) ) Kyu ranks are student ranks and go from 10th (white belt) to 1st (3rd degree brown belt). 1st kyu testing is kind of a big deal because it's the last one before black belt. #hardcorefighting