Moving on.

For anyone who missed it, back in September I decided to multi-task by letting my somewhat busted right hip/leg recover while also getting back to super slow, low-heart rate base training. The plan was to do nothing but sloooooow easy miles for eight weeks, then add in one goal marathon pace run per week.

This meant I went from running my easy and long runs in the 8:15-8:30 range to doing them in the 10:00-11:00 range. Which kind of might sound like a bummer, but once I adjusted to the slower pace, it was actually really nice and relaxing after a summer of marathon training.

Quick recap from this post on how base training helps make you faster:

- You can google all the biochemical details of how & why it works, but basically, when you spend hours and hours and hours each week bathing your cells in oxygen at a nice, easy effort level, a couple of things happen:

- 1) Your heart becomes more efficient at pumping blood. That is, you improve your "stroke volume"--how much blood your heart pumps out with each beat or "stroke." Stroke volume is important because the aerobic system relies on oxygen, so greater stroke volume = more oxygen delivered to cells more quickly with less work by your heart.

2) Your body becomes more efficient at using the oxygen you breathe in. That is, you improve your "running economy"--converting the same amount of oxygen into more forward motion. Part of this has to do with delivering more oxygen more quickly (more red blood cells, more myoglobin, etc.) and part of it has to do with cells using the oxygen they get more efficiently (more and bigger mitochondria, more enzymes for metabolizing fat efficiently, etc.)

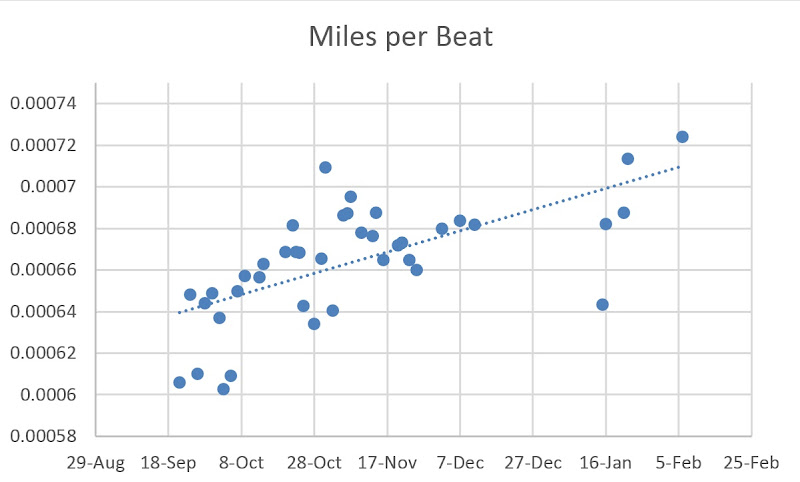

When you improve both of these things, the result is generating more forward motion with fewer heartbeats. So it seemed to me that the question I should be asking here is, How much forward motion am I generating per heartbeat?

So I collected my pace & heart rate data, graphed it, & at the end of eight weeks, my "miles per beat" had done this:

Base building: It may not be sexy, but it's got teeth.

I mean the trend here really shouldn't be all that unexpected; that's how training is supposed to work, right? Still, I was pretty pumped to see objective mathematical evidence.

After that I started doing one run a week at goal marathon pace (usually a two mile easy warm-up, six miles at goal marathon pace--around 8:00/mile--and a two mile easy cool down). I wasn't sure what would happen to my "miles per beat" numbers after that, and here is why.

In the course of reading about base training and speed work and the whole idea of periodization, I came across this article from Running Times, which explained the following:

- DON'T SABOTAGE YOUR BASE BUILDING. Arthur Lydiard learned this more than 50 years ago. Too much speed work in your base phase will interrupt your fitness development. Olympic bronze medalist Lorraine Moller, whose training was Lydiard-based, says that in the era of New Zealand track domination, "Going to the track to do speed work during the base phase was considered the height of folly and something only the ignorant would do."

...

Peter Snell, exercise physiologist and Lydiard's most famous runner, explains that the enzymes within the mitochondria operate at an optimal acidity (or pH) level. High-intensity exercise, however, causes significant and repeated high levels of lactic acid (and thus decreased pH) in the muscle cell. Given too much intensity, the environment within the cell becomes overly acidic and the enzymes can become damaged. Snell says that the increased acidity is also harmful to the membranes of the mitochondria, and it takes additional recovery time to allow the membranes to heal.

Given this damaging effect, large and frequent increases in lactic acid during a period when you're building your aerobic energy system (mitochondria and aerobic enzymes) are a big no-no.

So yeah, marathon pace is below LT pace, so it shouldn't do too much damage. Then again, right now, 8:00 miles are still GOAL marathon pace, not actual marathon pace, and during a normal week of training, they sure start to feel kind of hard by mile five or six. So I've been maybe a touch paranoid.

I haven't been tracking & recording my paces & average heart rate quite as assiduously since those first eight weeks, but I've recorded some numbers, and truth be told had been kind of avoiding plugging them into Excel because I didn't want to see that they'd plateaued or, worse, started to droop back down. So, after an extremely wet and windy run on Friday afternoon, I decided to finally just bite the bullet, for better or worse.

Behold:

Twenty weeks and still going.

There are a few interesting features to point out on this graph. First, that super low dot just a couple of weeks ago? One of my unhappiest sick/asthma days. And the two far and away highest ones (Oct. 31 & Feb. 6)? Both warmish, windy, and pouring rain.

I know that I tend to run significantly worse in warm weather (above 65 or 70) and that my fastest runs have been in cold-but-not-TOO-cold temps (mid-to-high 40s, say), but I've never particularly noticed any trend related to rain. I have been scouring the internet to see if there could be some physiological reason for it, but so far, nothing. I mean I could understand it if they'd been cool rains, but both days were mid sixties-ish.

(That Halloween run was particularly freakish. It was nearly three months--three months!--before I ran that efficiently again.)

The question at this point is when to start doing real speed work again, & what kind. After NVM on March 1, my goal race (Santa Rosa) will still be nearly six months away, which is way too long to do real speed work for. I need to figure out how many weeks will be just enough to let me "peak" without messing up my hard-won aerobic system too much. RunCoach is great at prescribing workouts on a day-to-day and week-to-week basis once you're really gunning for a goal race, but they're not so much with the periodization, so that is something I will probably have to get some additional advice about.

Yay for progress AND graphs with real data! The outliers are quite interesting too. I'm curious to see what/when/how you work in speed work!

ReplyDeleteI'm planning on focusing on speed through an early October half marathon then base building for a March marathon. Reading these updates continually and seeing this progress has been a real motivator to commit to base building pre-marathon.

ReplyDeleteI love running in the rain - altho' I always put that down to my British roots. I have zero data to back this up, but I always feel I perform well on a wet rainy run.

ReplyDeleteI can am beginning to appreciate more and more how professional athletes/coaches (as well as recreational runners) can get a kick (literally and figuratively) out of extremely detailed training and race reports: weather, HR, shoes, diet, rest, terrain, duration, distance, etc. Fun stuff!